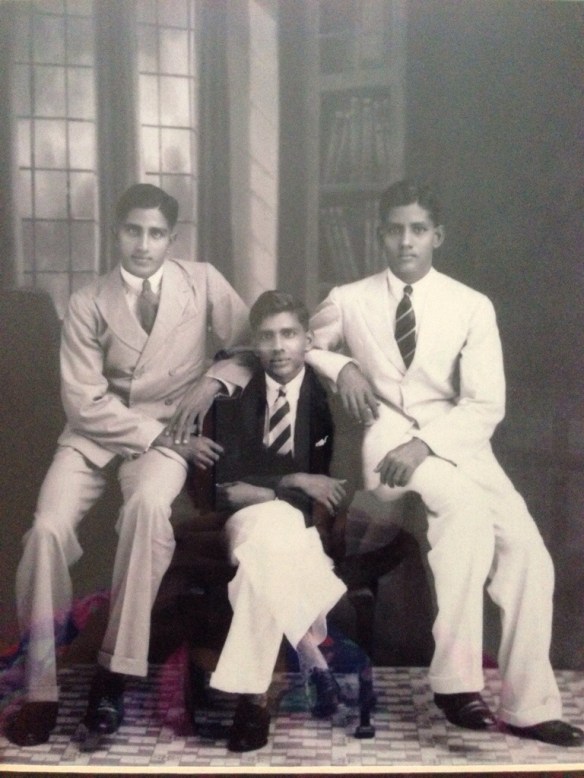

My grandfather (thatha), on the right.

Monthly Archives: December 2013

Haiku: Golden Trees

Golden trees alit

Dark clouds on the horizon

A storm approaches

Haiku: I dreamt of you

Once, I dreamt of you

Shimmered veils of paradise

Brought peace to my soul

Memoir Musings: The Blanket

“Can we get rid of this?” Pete asks, holding up a faded pink, patched cotton blanket. The stitching around the edges is unraveling, the label is faded, almost illegible from decades of use. I look up from the box I am packing with linens and sit back on my heels. I reach for it wordlessly, almost snatching it out of his grasp. “What is it?” he’s puzzled, it’s just an old blanket after all. Shaking my head, I ball it up in my hands, then smooth it out, feeling the incredibly soft fabric after all those years, the memories rushing back like freight trains, relentless, and I am helpless in their path.

I shake my head again, fold the blanket into a neat square and place it gently with the linens in the box. The next few hours fly by as we box up our life in the San Carlos house, getting it ready for the new owners. Our last night here, I think, looking around the living room that evening. “Go to bed,” he says, “I’ve got a few more things I want to do before I call it a night.” I nod and walk into the bedroom, gingerly picking my way past the debris on the floor. As I sit on the large, comfortable bed we share with our two greyhounds and three cats, I reach over to the box closest to me and unerringly pull out the pink blanket. Holding it close to my face, I draw a deep breath, imagining a faint odor of Old Spice and Brylcream. Leaning back against the soft pillows, I unfold the blanket and watch it billow slightly as I pull it up and over my face. The overhead light is now diffused, a pink fuzzy glow that grows and grows until it envelops me in its soothing warmth. As I lay there, my mind picking through the memories, the light lightens, brightens, changes from the warm pink to a stark yellow, harsh, insistent, painful.

The bed is hard and unyielding under me. I lie there, motionless; eyes open under the blanket, watching the black spots of floaters chase their way across my eyes. The overhead light seems hot on my face, through the blanket. I can hear the low murmur of voices in the distance, the occasional ring of the doorbell, visitors being ushered in, the clink of teacups, the long silences, the solitary sob.

I haven’t slept since my nap yesterday morning. We had come home from the hospital, exhausted, but happy. Thatha had shown a few signs of improvement: his face was showing more color, his lips moved, and I had felt his hand twitch under mine. Feeling hopeful, we took the chance to go home and bathe, change clothes, take a nap, and bring Paati back to the hospital.

When we returned, he was gone.

“Those are the typical signs of imminent death,” the doctor said. “They always look healthy right before they die. Color comes back into the cheeks, the breath smells sweet…” he shrugged, looked at us, nodded and then left us there, shell-shocked. I sat, tears pouring down my face, hugging myself. My mother and Paati sat motionless, disbelieving.

I don’t remember the ride home.

His body was brought home that evening. One of his sisters and other female relatives came around the same time, silent, efficient, helping to clear the space where he would lie for the night. They chose the open space where the dining and temple rooms opened onto, at the base of the stairs, the center of the house. All traditional Indian homes have a center, marked by a tile, different in shade to the surrounding flooring. Thatha had designed the house, and he had picked that spot as the center. A puja had been done by the Hindu priests to consecrate it, and finally, before the tile was set, a handful of precious jewels were placed there by my Thatha and Paati, the priests reciting the Sanskrit verses to bless the house and spread a veil of peace and safety over it. Over the years, the tile, specked with mica and other stones, had faded to a dull grey blue. I had whiled away long afternoons, wondering about the jewels hidden there.

The men from the hospital placed him on the floor, centering him over the tile. He lay there, looking as though he were just asleep. Paati sat down near his head, a relative on either side, ready to help her if needed. She sat there, looking at him, dry-eyed, focused. “He’s still breathing!” she gasped. Everyone looked at him, then at her, and one of the men said, sadly, “He’s gone, Amma.”

As the men walked away, she sat there, motionless, in disbelief. Then a harsh loud sob burst from her, followed by a keening, the like of which I’ve never heard before or since. It drove right into me, punching me breathless, and I fell to my knees. The women left her alone until she was spent, quiet, hoarse, hunched over by her husband’s head. Then they went to her, lifted her up to take her to her room, but she pushed them aside, insisting on staying where she was.

They then proceeded to undress him where he lay, oil and bathe him, and then cover his body with the traditional white sheets in which he would be cremated. I sat at his feet, unnoticed, undisturbed. When they were done, it was close to midnight. I looked around and realized that we were all women. All the men were gone, I knew not where.

One by one, the ladies fell asleep, until the only ones awake were me, my mother, and Paati. I looked at her, but her eyes were distant, lost. I slowly reached out to touch his feet, and then started massaging them, one last time, gently pushing on the strong bones, the prominent veins, the soft leathery skin. I didn’t think she noticed, but then as I was finishing, she said, “He always said you massaged his feet the best of all of us.”

I nodded, then lay down next to him, holding onto his foot, and we stayed there, Paati, my mother, and I, keeping vigil over his body through the night.

Early next morning, the men came, dressed in white lungis, the traditional wrapcloth worn by Tamil men. His brothers, my father, other male relatives and friends, they all came, to escort him to his cremation site. I prepared to go with them, but was met with the cold response from the priests, “It is no place for a woman.” My father didn’t make eye contact with me as I burst out crying, “I’m going with him!” They walked away, a procession of men, carrying away the only person who truly loved me, and who I loved. I followed them, out the gates, down the street, crying, until someone, I don’t know who, caught up to me and led me back home.

I follow their path in my mind.

I imagine this is what happens.

My father and male relatives are with him, a caravan of men dressed in white, taking him away, led by a priest, swinging a chalice with smoking ash. They chant as they go, the monotonous death chant. Passersby stop in respect, traffic gives way; no one crosses the path of the funeral procession. They arrive at the cremation site and they place him on the prepared logs of wood. As he has no sons, my father takes on the role of lighting the cremation pyre. As he walks up with the oil soaked stick, he starts to cry. He wonders briefly, is he really dead? He touches the lit stick to the pyre and then steps back, watching the fire catch, then flame and burn. He stands there, as close as he can, until the priests draw him away.

I imagine this is what happens.

I wait for them to return.

I wait a long time.

Someone tries to get me to bathe. “It is bad luck,” they say. “The spirit is still here. It doesn’t know what to do. It wants to stay where it is familiar. If you don’t wash the mark of death away, the spirit will attach itself to you. Come, come and bathe.”

The spirit is still here? He is still here?

I look around his room. I’m on his narrow bed, my head on his pillow, my body covered by his blanket. I wonder briefly at the oddity of a grown man having a pink blanket, and then I look around again. His clothes are in the closet, his favorite walking stick is by the bed, his spectacles are on his glass-topped desk.

His spirit is still here. I can feel him around me, I can smell his scent.

“I don’t care,” I say. “I want him to stay with me.”

They back away, making the signs to ward off evil. I laugh a little. As though my Thatha could ever be considered evil. “He can stay with me.”

I hear them talking to my mother outside the room. She responds, indistinct through the walls. She must have told them to leave me alone, because they do not return. I thank her silently.

I chase a floater across my eye, but it eludes me, staying just on the periphery of my vision. I close my eyes in frustration, but the floaters remain, my constant companions. I feel wetness build up behind my eyelids, leaking out the sides, down my face, pooling in my ears. I turn, curling up, folding myself into the blanket, making it a part of me, soft, filled with his familiar scent: Old Spice and Brylcream. It is mine now.

He doesn’t need it anymore.